‘Music is not meant to be something which exists alone’ – Satoshi Ashikawa.

Ambient music has long been a genre with an intimate connection to both imagined and specific spaces, rooted as far back as 1917 with Erik Satie’s seminal ‘Furniture Music’. In both the East and West, music with a direct function relating to space has found itself at the heart of ambient’s development, and the clearest, most explicit examples can be found in Japan’s pioneering 80’s ambient scene.

Translating directly to ‘Environmental Music’, ‘Kankyo Ongaku’ is a phrase used by Satoshi Ashikawa in the liner notes of his 1982 LP ‘Still Way’. This release is the second of a three-part project called ‘Wave Notation’, a series of tranquil, minimal and spacious ambient records released in Japan in the early 80’s. The liner notes of these releases form an eloquent manifesto of sorts from Ashikawa and Yoshimura, explaining this music’s function and context. It is not meant to distract the listener; it was created with the intention of surrounding them and transforming the space in which it is listened. Ashikawa noted that the music ‘should drift like smoke and become part of the environment’. This music, then, was made with its inseparable relationship to space kept in mind. The story of ‘Kankyo Ongaku’ starts with Hiroshi Yoshimura’s ‘Music for Nine Post Cards’ (1982), the first Wave Notation release.

Yoshimura was a pivotal figure in Japan’s newly resurgent 80’s ambient scene – his record ‘Green’ (1986) has become one of the most inspirational and central albums of the genre, and ‘Nine Post Cards’ marked his first official release. In its liner notes, Yoshimura discusses how the album was directly inspired by the architecture and scenery of the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in Shinigawa, Tokyo, which he visited while composing it. He was inspired by its minimal ‘snow-white Art-Deco style’ and the courtyards trees framed by the museum’s large window. Exploring the museum, he felt this release he was working on could ‘possibly be one of the best sounds that fit this environment’.

Newly stimulated by this architecture, he finished the record and approached the museum’s administrators, who gladly agreed to play it to soundtrack the art. Ashikawa later released it as the first record in the ‘Wave Notation’ series, a series dedicated to publishing this environmental music. The records warm, minimal tones and gently evolving phrases leave enough space for contemplation, yet also provide a comforting ambience that can absorb floating thoughts as one’s environment is enveloped by the sound. Yoshimura also composed music for plenty of other spaces, including train stations, galleries, and even prefab homes for the Misawa corporation in 1986. He was able to tap in to the inherent emotionality and atmosphere certain spaces hold, creating music that subtly sits amongst and intensifies it.

While Ashikawa and Yoshimura were among the first to discuss the intricacies and intention of their sound design, this practise of creating ambient music with specific spaces in mind is not just the preserve of ‘Kankyo Ongaku’. Eno’s pivotal ‘Ambient 1: Music for Airports’ (1978) is the most obvious other example to Western audiences (although this was for a more imagined, non specific space than the tangible locations Yoshimura was making music for). Nonetheless, something about the nature of ambient music means it has an ability to function as part of a space, as opposed to just a musical addition to it. To discuss this further, it’s worth considering another prime example, bringing us to Haroumi Hosono of ‘The Yellow Magic Orchestra’.

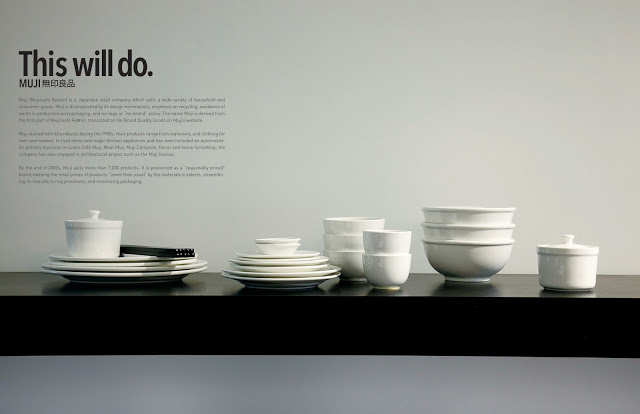

In 1984, Hosono was approached by the Japanese retailer Muji and commissioned to produce music to be played in their stores. He came up with a tape of meditative, pensive ambient, clearly produced with the ethos and architecture of the stores in mind. These stores focus on a minimalist, spacious layout – clean, flowing and understated, much like the music itself. The emotive, gently looping chord progressions of this B side seem to float in empty space. Combined with the related aesthetic of the Muji stores, this music functioned as sound art in a space it was specifically composed to fit.

The 80’s Japanese ambient movement has seen a recent boom in popularity. This is predominantly due to a combination of factors – the fetishization of rare records and cassettes in the Discogs era combined with Youtube’s ability to bring relatively obscure records from a localised scene to hundreds of thousands of new listeners internationally. Not only is the listenership of this music increasing, but plenty of modern producers are now creating what is undeniably environmental music of the kind Ashikawa envisioned. For instance, London’s ‘Local Action’ put out the sublime ‘Spa Commisions’ LP by Yamaneko last year.

Yamaneko draws equally from grime, new age, video game music and more recently trance to produce blissful, immersive ambient – staggeringly contemporary and original, yet clearly influenced by the 80’s new age of Yoshimura and co. This ‘Spa Commisions’ album was, as implied, originally produced to be played in some unnamed spa in Europe. Eventually (like ‘Nine Post Cards’) it found another home with a label and was released officially. Created with a specific space in mind, this LP is a perfect example of modern environmental music.

Yamaneko works alongside Deadboy, India Jordan and others to run the ‘New Atlantis’ project – a London based ‘ambient social’ and label. Nestled in the Rye Wax basement just off bustling Rye Lane, New Atlantis put on one of London’s only regular ambient events one Sunday a month, providing some respite from the invasive sonic overload of the city.

Ashikawa and contemporaries put forward this idea that ambient music provides a welcome break from the overwhelming noise of late capitalist urban society, and modern examples (like New Atlantis, Spa Commissions) cement the relevance of these observations. Midori Takada (who’s 1983 LP ‘Through the Looking Glass’ sits alongside Yoshimura’s ‘Green’ as one of the most seminal ambient records to come from Japan in the 80’s) once said in an interview that ‘everything on earth has a sound’. Similarly, Ashikawa noted that modern life in industrialised Japan was ‘inundated with sound’, and as a society, we should pay more attention to the sounds around us and attempt to take control. He posited environmental music as a step towards individualistic agency over the sounds we are exposed to, claiming we should ‘treat sound and music with the same level of daily need as we treat architecture, interior design, food, or the air we breathe.’

The natural, organic sounding ambient music Ashikawa and Yoshimura were creating was not simply an ode to Japan’s tranquil countryside, but an active push back at the increasing suffocation of urban society. Yoshimura created still, natural, watery textures and soundscapes (notably so on ‘Green’, arguably his most organic sounding record), yet did so with digital synthesisers in the heart of noisy industrial Tokyo – an interesting collision of the natural with the urban. This music was created in an era of increasingly widespread environmentalist philosophy in response to Japan’s industrialisation and rapidly changing landscapes. The presence of modern environmental music is testament to the ongoing relevance of Ashikawa’s ideas – with the ever increasing detachment from nature, we look to the organic stillness and pure naturalism of environmental music to escape the all-encompassing noise of modern urbanity. Yoshimura has said of ‘Nine Post Cards’ that he was trying to provide ‘images of the movement of clouds, the shade of a tree in summer time, the sound of rain, the snow in a town’ – images and feelings we must now be careful not to forget.